|

| Book!! |

Camels!! is a

rather plain looking maroon clothbound book outside of the fact that it was

angry about humped mammals for some reason. Yes, angry – excitement and

surprise stops with one exclamation mark. The 277 pages were printed on heavy

stock, making the book appear denser than it actually was. Written by Daniel W.

Streeter, this copy was a fifth edition printed in 1928, which lead me to

believe that his feelings on desert beasts of burden were shared by many in the

early 20th century.

|

| Middle East was often confused with Middle Earth. |

Camels!!, it turns

out has very little to do with actual camels. Much like Lands and People from

two weeks ago, the cover was nothing but a tease. From the table of contents,

this book appeared to be a text on explaining male mating habits with the two main

sections titled: “Why Men Do it?” and “Why Men Do Do It”.

|

| Do what? |

And indeed, this book is a fascinating tale, no doubt a bit

exaggerated, about a man on an early adult rite of passage traveling the

Middle East whilst fighting/seeking temptation. Halfway into the first chapter,

the tone, subjects, and language made it wholly possible that a writer from one

of the many men’s magazines that flooded the market a few years ago had written

this, printed it out on old paper, aged the book, and hid it in a book store simply

to troll anyone who picked it up expecting humped animals. If Hemingway was a

1920s frat boy, this would be his Sun

Also Rises.

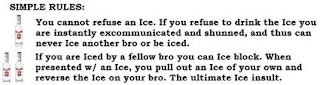

With lines like “I’ve had my fling. I can’t go rushing about

all over the place. I’ve got obligations, man – I don’t know what they are

exactly, but I’ve got ‘em”, I was quite surprised the narrator did not present

his mates with a case of Smirnoff refreshments to partake in the age-old

pastime of brethren icing brethren.

|

| Yes, it is a thing. |

Filled with a wealth of anecdotes that straddle the line

between far-fetched and sheer absurdity, it was hard to not cry bullshit at every

other page. Case in point - a suicide jumper leaps from a bridge and changes

his mind when he hits the water, screaming for help. Instead of assisting, the

crowd mills about debating his nationality until the police-boat fetched him

out of the water… and arrested him for fishing without a license.

Interlaced between these accounts of his travels, though,

were photographs documenting the areas the narrator visits, which was a brilliant

device to lend credibility to the tall tales. Eventually the narrator does end up

running into the eponymous camels (!!), and promptly rides them into the desert

to shoot other animals with disastrous results – “Charged by an infuriated

buffalo – touchy animal – all we did was shoot at him.”

|

| Cheetah cat ferret squirrels grow on trees apparently. |

The disjointed narrative hops from observation to embellished

observation in a very brisk manner that encapsulates the atmosphere of

listening to a university friend recount their tale of that time they went on a

bender and woke up in Tijuana, but told as if they were pressed for time and

yet needed to describe every single detail of their trip.

|

| Much like Australia, everything there wants to kill you. |

The prose is dry, sarcastic and rather uncouth, which made

it extremely enjoyable to read. With many exchanges playing out like a comedy

routine, (“About these camels, the first thing is to get their humps

straightened out-” “What do you mean – a little plastic surgery?”) this book was

one of the few I have read in many years that ended far too early. Immature and

always finding ways to get himself into bad situations, the narrator is the

embodiment of my inner child.

Dashed curious.

Book rating:

10/10 (The most entertaining of all the Biblio-Mat books read so far. Humourous

and worldly, highly recommended.)

Random quote: “We

connected with our camels, sometimes called “Ships of the Desert”, by people

who don’t care what they say.”